|

3/19/2015

By Carol Beuchat PhD

Although Gregor Mendel is the father of modern genetics, Jay Lush is the fellow who brought genetics to animal breeding. Lush was a student of Sewall Wright, who devised the coefficient of inbreeding, and a background in both genetics and mathematics allowed him to develop animal breeding into a quantitative science. Perhaps his most important contribution is a book first published in 1937 called Animal Breeding Plans, in which he laid the foundations on which the scientific breeding of both animals and plants still rest today. While parts are necessarily outdated now, much of what he wrote is as useful today as it was then.

Most breeders know about inbreeding and linebreeding but find it difficult to clearly distinguish between them. Usually inbreeding is considered to be breeding among first-order relatives (e.g., sibling to sibling, parent to offspring), and linebreeding is a fuzzy version of "not as close as inbreeding". When Lush discusses linebreeding in his book, though, he clearly distinguishes between linebreeding and what he calls "other forms of inbreeding", which he simply defines as breeding between relatives.

Lush describes linebreeding as a very special form of breeding.

"Linebreeding, more than any other breeding system, combines selection with inbreeding. In a certain sense, linebreeding is selection among the ancestors rather than among living animals... It is accomplished by using for parents animals which are both closely related to the admired ancestor but are little if at all related to each other through any other ancestors. If both parents are descended from the animal toward which the linebreeding is being directed, they are related to each other and their mating is a form of inbreeding in the broad sense of the word."

This is worth saying again. According to Lush, linebreeding pairs animals that are related to a specific ancestor, but which are little if at all related to each other.

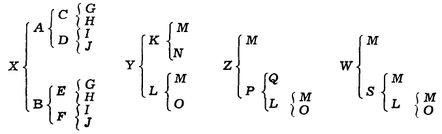

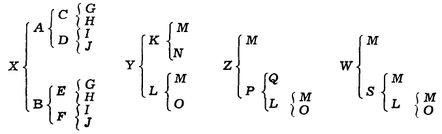

To illustrate his point, he offers some simple pedigrees.

He says, "the parents of X are double first cousins, having the same four grandparents. The parents of Y are half brother and sister. Z is produced by mating a sire to his own granddaughter. W is produced by mating a sire to his daughter out of one of his own daughters. The intensity of the inbreeding is the same for X, Y, and Z. Yet X would rarely if ever be called linebred. Its sire and its dam are related through four different ancestors which, so far as the pedigree shows, may belong to four unrelated strains. If a breeder were to call X linebred, he would have to say that it was linebred to four different lines at once, which is something of a contradiction in terms. He would call Y linebred to M because K and L are related only through M, and Y has been kept almost as closely related to M as it parents were. Z is even more clearly a case of linebreeding because it is more closely related to M than Y is, although no more intensely inbred. Many breeders would call W inbred instead of linebred because the intensity of its inbreeding is so high. Others would call it "intensely linebred to M," since all of its inbreeding is focused on M and it contains 87.5% of the blood of M - a relationship of 75% after allowing for W's inbreeding."

Lush saw linebreeding as a way to preserve an exceptional ancestor's influence. For every generation that passes between the ancestor and the present, its influence is reduced by half. To avoid this progressive dilution, "linebreeding takes advantage of the laws of probability as they affect Mendelian inheritance to hold the expected amount of inheritance from an admired ancestor at a nearly constant level...Linebreeding provides, so to speak, a ratchet mechanism for holding any gains already made by selection, while attempting to make further gains."

A significant advantage of linebreeding over ordinary inbreeding is that, while it also increases homozygosity and prepotency, "the homozygosis produced by linebreeding is more apt to be for desired traits than is the case with undirected inbreeding. Linebreeding tends to separate the breed into distinct families, each closely related to some admired ancestor, between which effective selection can be practiced."

Don't miss the significance of this last point. Lush is saying that if there are multiple lines of animals linebred to a common ancestor, the breeder can manage inbreeding by using those groups as a source of animals for outcrossing while still maintaining the strong genetic influence of the ancestor. And because these groups of animals have not been interbreeding, they can be used to produce offspring that will have a lower rather higher inbreeding coefficient, and thus will benefit from hybrid vigor (a reduction in inbreeding depression) as well as a diminished risk of genetic disorders caused by recessive mutations.

There are dangers to linebreeding, one of which is that if too intense it will result in fixation (homozygosity) of undesirable genes. Lush was very clear on the deleterious effects of inbreeding, which he called "inbreeding degeneration". He advises breeders to avoid all inbreeding that is not necessary for maintaining the relationship on the line bred animal so that the inbreeding intensity remains modest. Indeed, he points out that the gains to be made by linebreeding to a mediocre ancestor might not balance the loss of quality (his "degeneration") expected to result from inbreeding.

To linebreed successfully to a particular animal, it must have enough offspring so that linebreeding to its own descendants can be avoided. For a dog breeder to be able to do this, it might require keeping around more dogs than one breeder can accommodate, but a group of breeders with common goals can cooperate in breeding towards the same line and using each other's kennels for the occasional mild outcross.

Lush transformed the science of animal breeding over 70 years ago, and the revolution he started has stood the test of time. The advent of reproductive technologies and DNA analysis have changed the processes of breeding and selection considerably since his day, but his insights into genetics were sound and are still the basis of animal breeding to this day.

|